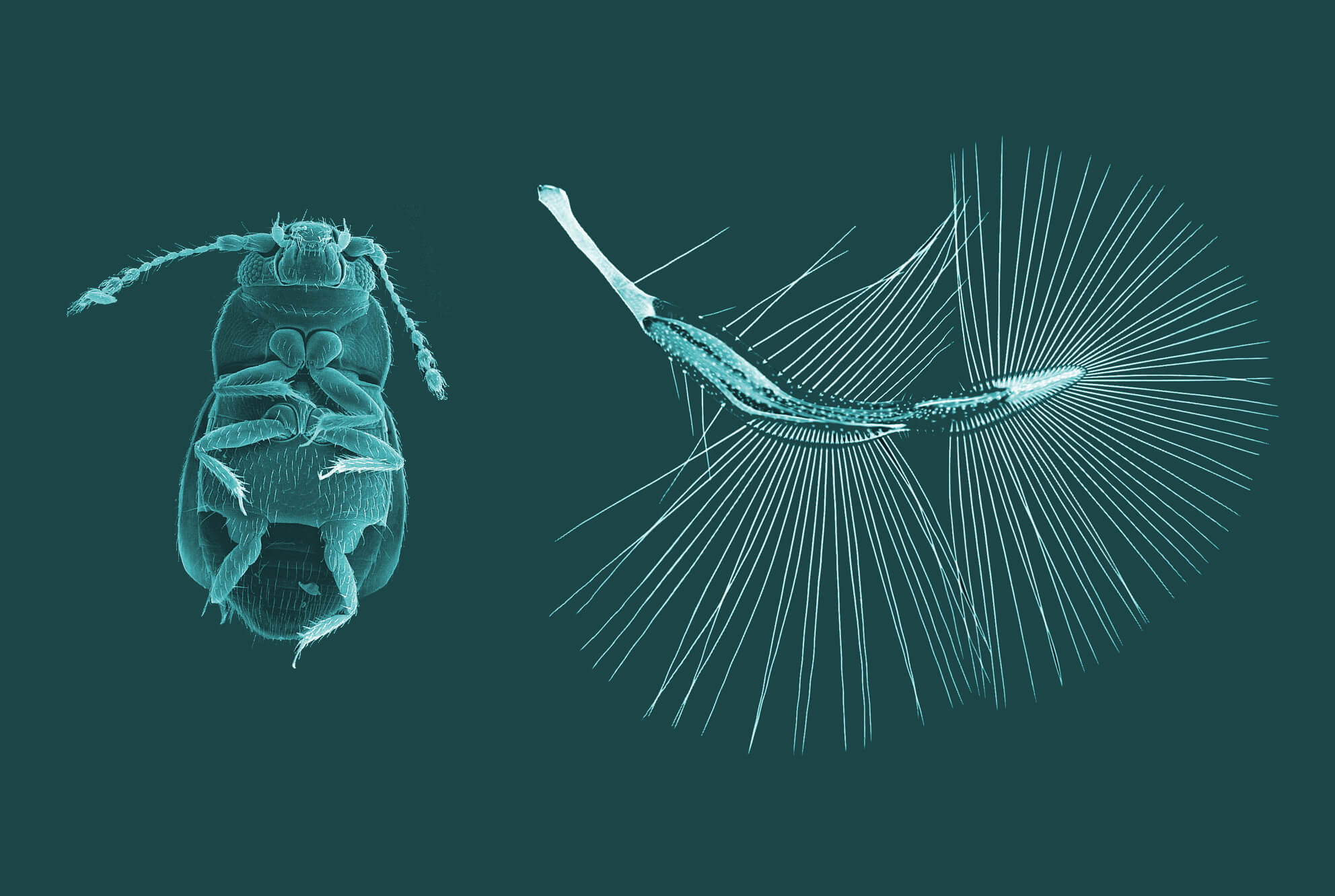

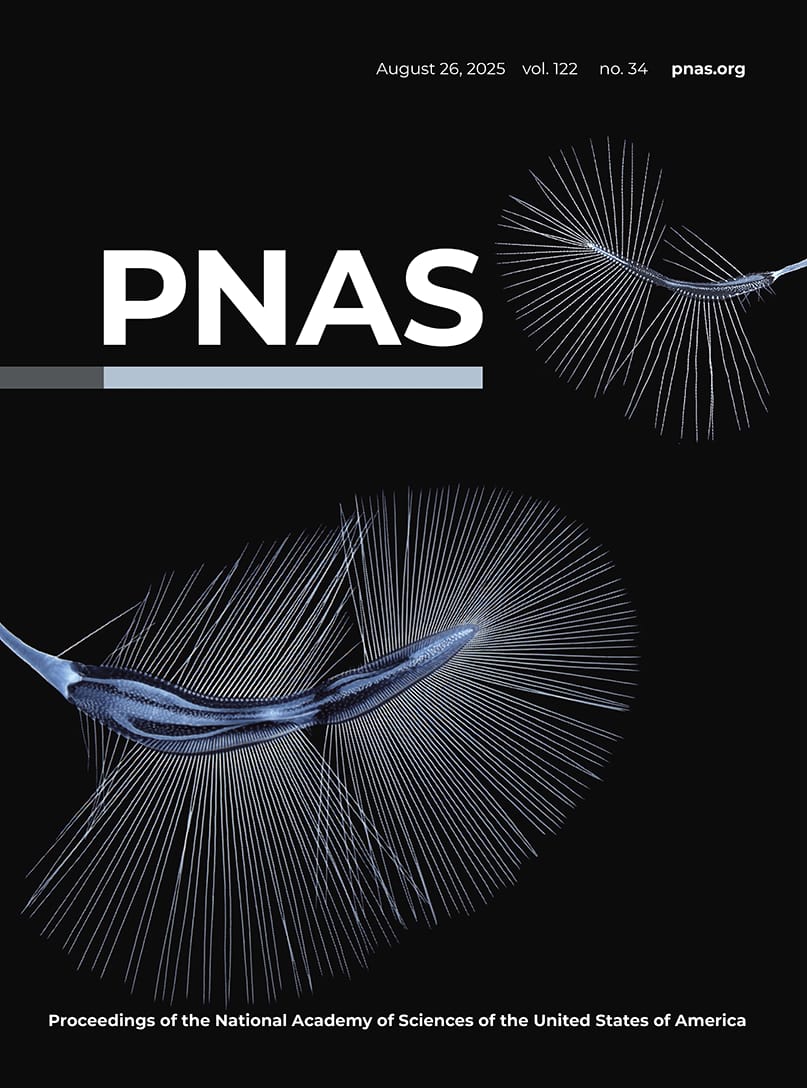

Skoltech and MSU scientists have uncovered the advantage gained by microscopic bugs from their featherlike wings that are unlike those of dragonflies, bees, mosquitoes and other familiar insects. A wing largely made up of bristles that stand somewhat apart from each other is lighter than the conventional membranous wing that comes in one piece. This advantage is crucial for microinsects, which are strongly affected by air resistance. They overcome it with wing motions reminiscent of those made by oars in rowing. The findings could come in handy when the miniaturization of insect-sized unmanned aerial vehicles reaches these truly tiny, submillimeter dimensions. Backed by a Russian Science Foundation grant, the study came out in the journal PNAS and appeared on the cover of the issue.

Small-scale drones that mimic some of the features observed in insects so far remain a lab curiosity, but with further advances in technology they could prove useful for collecting information where compact size, unobtrusiveness, or stealth are of the essence. Someday swarms of insect-inspired drones could become viable for search-and-rescue operations, infrastructure monitoring in tight spaces, such as in elevator or ventilation shafts, observing wild animals in nature, or gathering intel.

The smallest controllable drones are the University of Pennsylvania’s Piccolissimo (2016), which measures 2.5 centimeters and weighs 2.5 grams, Harvard’s 3-centimeter RoboBee (2012), and the recently unveiled 1.5-centimeter, 0.3-gram mosquito drone (2025) created at China’s National University of Defense Technology. The latter two rely on winged flight. Propellers, notably, tend to create more noise and cause greater damage in the event of a collision.

What hampers further miniaturization apart from the obvious challenges with battery size is the mechanics of flight itself. Taking microbugs as an example, on such a small scale, the forces of viscous air friction turn out to be comparable to the forces of inertia of a flying insect. It therefore becomes more difficult for these flyers to “wade” through the air than for larger creatures. Accordingly, the wings of the smallest insects are arranged in an unexpected way.

“It has long been known that the size of about a millimeter presents something of a division line, where larger insects have familiar membranous wings and many of the smaller-sized species employ wings consisting of separate bristles with intervals between them. It was unclear why,” said the lead author of the study, Assistant Professor Dmitry Kolomenskiy of Skoltech Materials.