Relying on rugged lava fields, a plethora of psychological screening tests and dozens of die-hard volunteers, Professor Kim Binsted of the University of Hawaii has made it her mission to identify the types of people best suited for life on Mars.

According to billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk, it’s not a matter of if – but rather when – an apocalyptic scenario will render the planet Earth effectively incapable of sustaining human life.

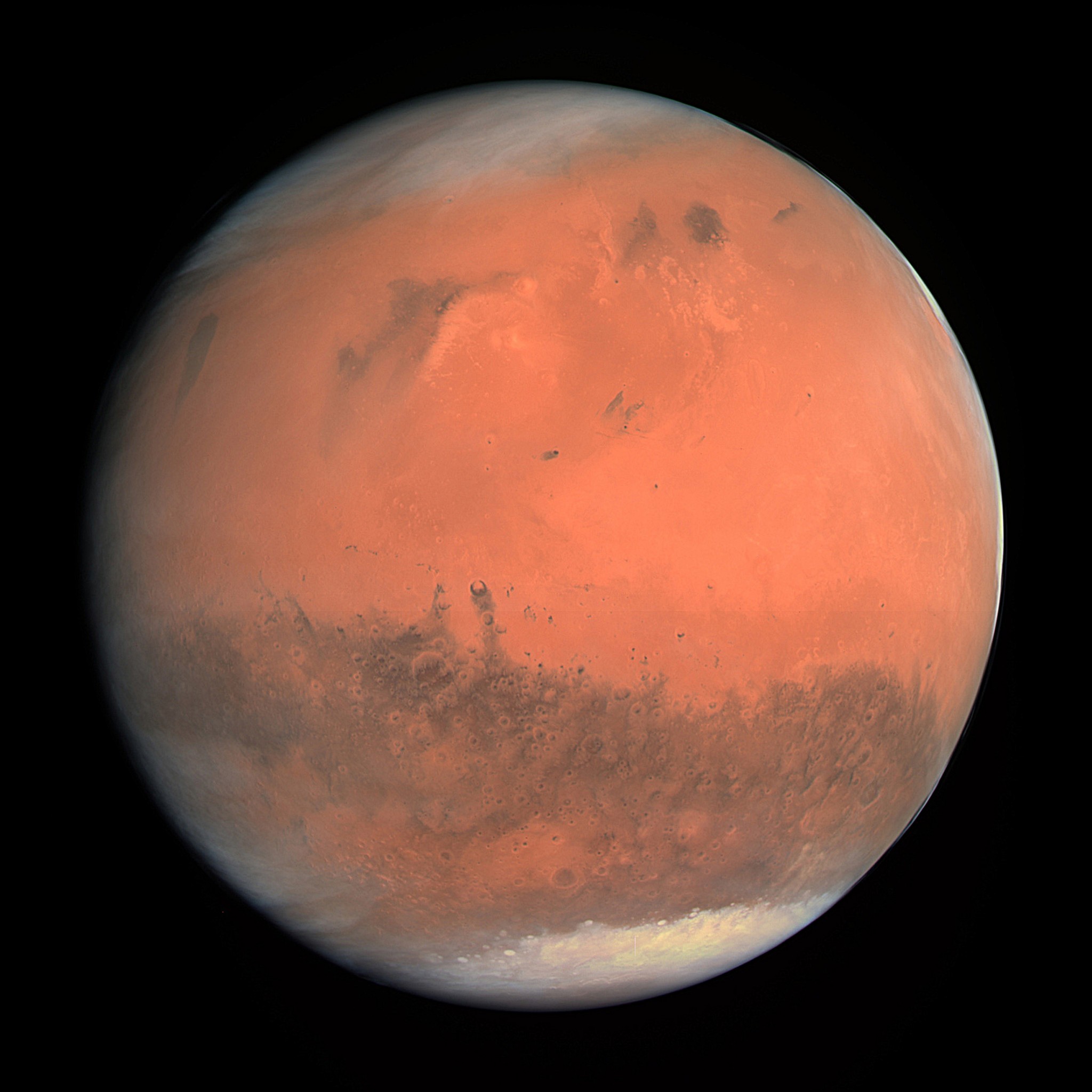

And when that day comes, humanity will have two options: we can accept our doom, or leave the world behind, moving on to redder pastures.

“I think there are really two fundamental paths,” Musk said in a talk on the plans of his company SpaceX to colonize Mars. “History is going to bifurcate along two directions: One path is we stay on Earth forever, and then there will be some eventual extinction event… some doomsday event. The alternative is to become a space-faring civilization and a multi-planet species, which I hope you would agree… is the right way to go.”

Just a few years ago, the idea of a human civilization on Mars could easily have been written off as the stuff of science-fiction fantasy.

But for a growing number of space agencies, private companies and scientific researchers, the prospect of life on the Red Planet has become an imminent reality. The US space agency, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), for its part, has predicted that the first humans will fly to Mars in the 2030s, while SpaceX has the more ambitious goal of 2022.

These dates are just around the corner, raising the important question of who will be the first to go.

At present, scientists around the globe are tackling a vast array of issues specific to human life on Mars – issues ranging from perchlorates to micro-gravity, from life-saving technologies to bio-regeneration and from sleep studies to interstellar psychological treatments.

As part of this expansive patchwork of research, Binsted has devoted her career to ascertaining how the human mind will react and adapt to deep space travel and to life on Mars.

Binsted, who is currently based in Moscow on a Fulbright fellowship, recently delivered a guest lecture at Skoltech. We caught up with her to learn more about what sort of person would be the ideal interplanetary pioneer.

Life on Mauna Loa is not for the faint of heart

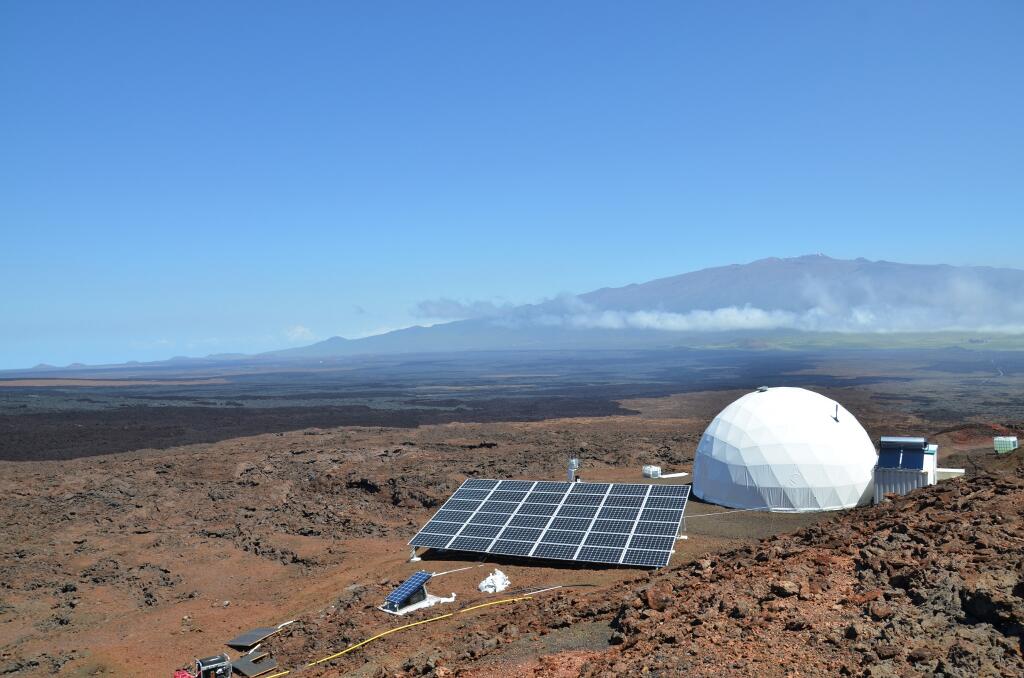

Binsted serves as principal investigator of HI-SEAS (Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation) – a habitat built in a Mars-like environment on isolated lava fields on the Mauna Loa volcano some 8,000 feet above sea level on the island of Hawaii. Volunteers take up residence in the habitat for periods ranging from four months to a year, and live as if they were residing on the Red Planet.

The habitat measures 1,200 square feet – about half the size of your typical tennis court – and for anyone with a tendency toward claustrophobia, the struggle is compounded by the fact that all communal spaces are to be shared for months on end with five other people who at first are total strangers, and with whom there is no guarantee of social camaraderie.

Add to that the facts that food supplies are strictly regimented, communications with the outside world are subject to substantial time delays (20 minutes for each incoming or outgoing email) and water is limited – a reality that at times has drummed up competitions to see who can go the longest without washing their clothes or bathing. In one case, Binsted recalled, a crew member went four months without a shower. Fortunately for his habitat mates, he is said to have used inventive means to maintain decent personal hygiene throughout.

And forget about going out for a quick walk to escape the confines of the habitat; to venture outside, all participants must wear a mock space suit and scale the rocky, unforgiving slopes of the Mauna Loa lava fields.

Combined, these factors would be enough to drive many otherwise well-adjusted people over the edge. And this is precisely why HI-SEAS exists.

All of the rules at the Mauna Loa site are rooted in the stark realities of the Mars the first human explorers will encounter. And with the first Mars mission expected to take place within the next couple of decades, it is crucial for researchers to determine who among us is best equipped to persevere in the face of the planet’s innumerable stressors.

From Artificial Intelligence to deep-space psychology

Binsted began her scientific career as a specialist in Artificial Intelligence (AI). A passion for cognitive science and a lengthy Arctic expedition ultimately paved her way to the helm of HI-SEAS and cemented her status as an authority on the types of people best suited for Mars.

At Binsted’s alma mater, the University of Edinburgh, the study of AI is rooted in Epistemology – the philosophical study of knowledge. As such, her education there involved a great deal of cognitive science and psychology.

After spending a couple of years working as a human-computer interface researcher for Sony in Tokyo, Binsted’s longtime interest in space travel led her to a summer faculty fellowship in the Neuroengineering Lab of NASA’s Ames Research Center in California. In the years that followed, she held various scientific roles with NASA and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA).

Her growing enthusiasm for space led her to serve as chief scientist on FMARS 2007 – a four-month Mars exploration analogue mission conducted in the Canadian Artic in 2007. It was her experience on this mission that ultimately laid the foundations for HI-SEAS.

“The mission really got me thinking about the psychology of these teams, which led to my current research,” Binsted explained.

While participating in FMARS 2007, she experienced several of the difficulties that HI-SEAS strives to deal with today, including combatting the crew-ground disconnect – a common issue where resentment develops between crew members and mission support, hindering effective communications.

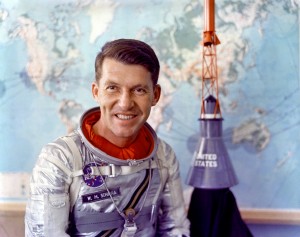

US astronaut Wally Schirra, whose Apollo 7 mission culminated in a legendary case of crew-ground disconnect. Photo: NASA // Wikimedia Commons.

A famous example of crew-ground disconnect was seen in the Apollo 7 mission of 1968. Battling a bad head cold and disgruntled with what he saw as the conflicting priorities of ground control, Wally Schirra – one of the original US astronauts and the first person to fly to space three times – refused to follow several orders from ground control, and ultimately told members of NASA’s top brass to “go to Hell.”

Of her own crew’s run-in with crew-ground disconnect, Binsted said: “I found it really striking that we experienced it, because we had been warned that the crew-ground disconnect could be an issue going in, and I thought, ‘We’ve been warned, so we won’t do that,’ and that’s not how it works. Even though you know it can be a problem and you’re intent on avoiding it, it still happens.”

After receiving funding from NASA’s Human Research Program, HI-SEAS launched its first study in 2013, and has continued to monitor crews of international volunteers ever since. Binsted and her team are driven chiefly by the goal of reducing the risks associated with long-duration space travel, specifically by developing a comprehensive understanding of the psychological profiles and personality types most likely to flourish on Mars and in other deep-space missions.

Painting a picture of the ideal deep-space astronaut

Despite the tough conditions of life on Mauna Loa, hundreds of applications from all over the world pour in following each of HI-SEAS’ open recruitment calls.

Applications are initially narrowed down by a set of base-level qualifications. At this stage, the HI-SEAS team also considers each candidate’s motive. One application that was fairly quickly tossed into the reject pile was written by a father on behalf of his eight-year-old son. Spain’s economic crisis also lured in scores of applications from job seekers who simply wanted to generate income.

Rather than relying solely on interviews when narrowing down the candidate pool, the HI-SEAS team runs a battery of cognitive and personality assessments to gauge each candidate’s psychological fitness for a Mars mission.

It being a NASA-funded operation, one might assume that the US space agency has drawn up a profile of the ideal astronaut and instructed HI-SEAS to seek candidates that most closely resemble that ideal.

To the contrary, NASA has not disclosed its psychological criteria or preferences to HI-SEAS; information such as this is subject to strict confidentiality in order to deter would-be astronauts from gaming space agencies’ candidacy processes.

As such, HI-SEAS has been left to its own devices to ascertain who would best fill the role.

Toward this end, Binsted and her team have pored over the astronauts that NASA has selected in recent years, assessing their psychological and personality characteristics to the furthest extent possible.

To fill in the remaining gaps, they have manned their crews with candidates whose personalities seem to have the greatest potential for success, and adjusted their findings based on their observations of how different personality types tend to interact during missions.

“You’re looking for someone who has a thick skin, a long fuse and an optimistic outlook,” she said, citing a colleague’s summary of the process. “And I would add to that – easily entertained. If you’re the sort of person who needs to go out clubbing every weekend, or the type who needs to go on long hikes outdoors in the countryside, you’re not going to be happy. You need to be the sort of person who can look at a cat video, and have that be enough.”

She noted that a key factor is finding candidates whose personalities strike the ideal balance between introversion and extroversion. “You want someone who’s comfortable in close quarters with other people, which requires a certain degree of extroversion, but you don’t want someone who needs to meet people all the time,” she said.

Likewise, extreme personality traits of any variety tend to be strong deterrents in the recruitment process. “We know, for example, that if someone is very neurotic, that’s probably not a good match,” she said. “Really, any sort of extreme personality type wouldn’t be all that good for a Mars mission.”

And ultimately, the team remains open to trial and error in expanding their understanding of what sort of person could flourish in deep space. “In some cases, we don’t know which personalities are best for this sort of mission, so we’re collecting that as data,” she said.

“I can say pretty firmly that there’s no ideal model of the perfect astronaut,” she added. “There’s a range – and in fact you want a range – of types of people on a good crew. Putting together a good crew is not just picking the six that are closest to some ideal. It’s more like assembling a toolbox.”

Staving off conflict

Selecting unique but compatible crewmembers is essential not only to the technical success of the mission – but also to ensuring harmony both between the crew and mission support, and among crewmembers.

A key issue at play in crew-ground disconnects is the significant time delay in communications. “The thing with these missions: when you have a communication problem here on earth, you have lots of ways of addressing it,” Binsted said.

In real time, we tend to give each other instantaneous cues during conversations – like nods and facial expressions that indicate everything from our level of understanding to our emotional reactions. These cues create the opportunity to clear up misunderstandings as they occur.

In contrast, the communication delays that are currently an inescapable reality of deep space travel are fraught with opportunities for miscommunications, as well as ample time to stew over them.

“Most people have had the experience of sending an email that was misinterpreted by the recipient. Multiply that times all of your communication – so suddenly all of your communication is subject to these misunderstandings; none of it is happening in real time,” Binsted explained.

And crew-ground miscommunications are further complicated by the unavailability of normal approaches to deescalating conflicts. If you have a conflict with a colleague in your office, Binsted explained, you might reach out to your manager or invite your colleague out for a beer to patch things up. When you’re separated by hundreds of millions of miles, you simply don’t have these options to fall back on.

To reduce the likelihood of a serious crew-ground disconnect, Binsted and her team scrupulously warn incoming HI-SEAS crews about the likelihood they’ll occur, as awareness can help stave off growing conflicts.

Among crewmembers, even real-time communications are tested when several seasoned professionals are stuck in close quarters together for months on end.

To temper the likelihood of infighting, Binsted aims to select candidates whose personalities and skill sets will complement those of the other crew members, while also taking care to prevent the formations of competing cliques.

In particular, they try to avoid clear demographic splits; while they might select three men and three women, and three engineers and three scientists, they will not select three male engineers and three female scientists, as this could very easily create a rift within the habitat.

With all of these factors in mind, conflict remains unavoidable. Binsted explained: “You need to pick crew members who are resilient and can get over conflicts as quickly as possible.” Toward this end, they generally strive to select candidates who have tested and proved their resilience in the past by having worked in high-stakes atmospheres where lives were at risk.

So far, their efforts have paid off. “We haven’t had to pull anyone out for social complaints, but it’s been close,” she said.

Bridging the gap between Mauna Loa and Mars

SpaceX founder Elon Musk (second from right) pictured with former US president Barack Obama at a SpaceX launch site in 2010. Photo: NASA // Wikipedia.

One difficulty that HI-SEAS faces in recruiting mission crews similar to those that will man the first Mars missions is the age gap. The applicants most willing to spend several months living in Spartan conditions on the slopes of Mauna Loa tend to be between their late twenties and mid-thirties, whereas the first crew of Mars-bound astronauts is expected to be in their forties or fifties upon deployment.

“There are a couple of reasons why a Mars crew is likely to be older,” Binsted said. “One is they’re going to be more experienced, and space agencies are going to want their most experienced people. But also, because of the length of the mission and the radiation exposure, it’s going to be their last mission as it will put them at their maximum career radiation exposure limit. They’re not going to fly again after that.”

And inevitably, there will be significant risk involved in the mission.

As stated by Musk during his SpaceX talk: “The first journey to Mars is going to be really very dangerous. The risk of fatality will be high; there’s just no way around it… It would be basically: are you prepared to die, and if that’s ok, you’re a candidate for going.”

In this regard, Binsted noted that researchers are perpetually striving to reduce risks wherever possible, “but it’s still a very hazardous mission,” she said.

In his SpaceX talk, Musk explained that Mars represents two overarching goals. On one hand, by giving humans an alternative to planet Earth, Mars represents the aim of: “protecting life and ensuring that the light of consciousness is not extinguished.”

He went on: “but the argument I actually find most compelling is that it would be an incredible adventure. It would be the most inspiring thing that I could possibly imagine. And life needs to be about more than just solving problems every day.”

By scouring the globe for those among us who are adventurous but tame, introverted but extroverted, confident but measured, and who can derive true joy from a good cat video – Binsted and her crew are bringing the dream of an interplanetary humanity closer to fruition.