A rapt audience pictured during hte conference “Perspectives on High-Temperature Superconductivity.” Photo: Skoltech.

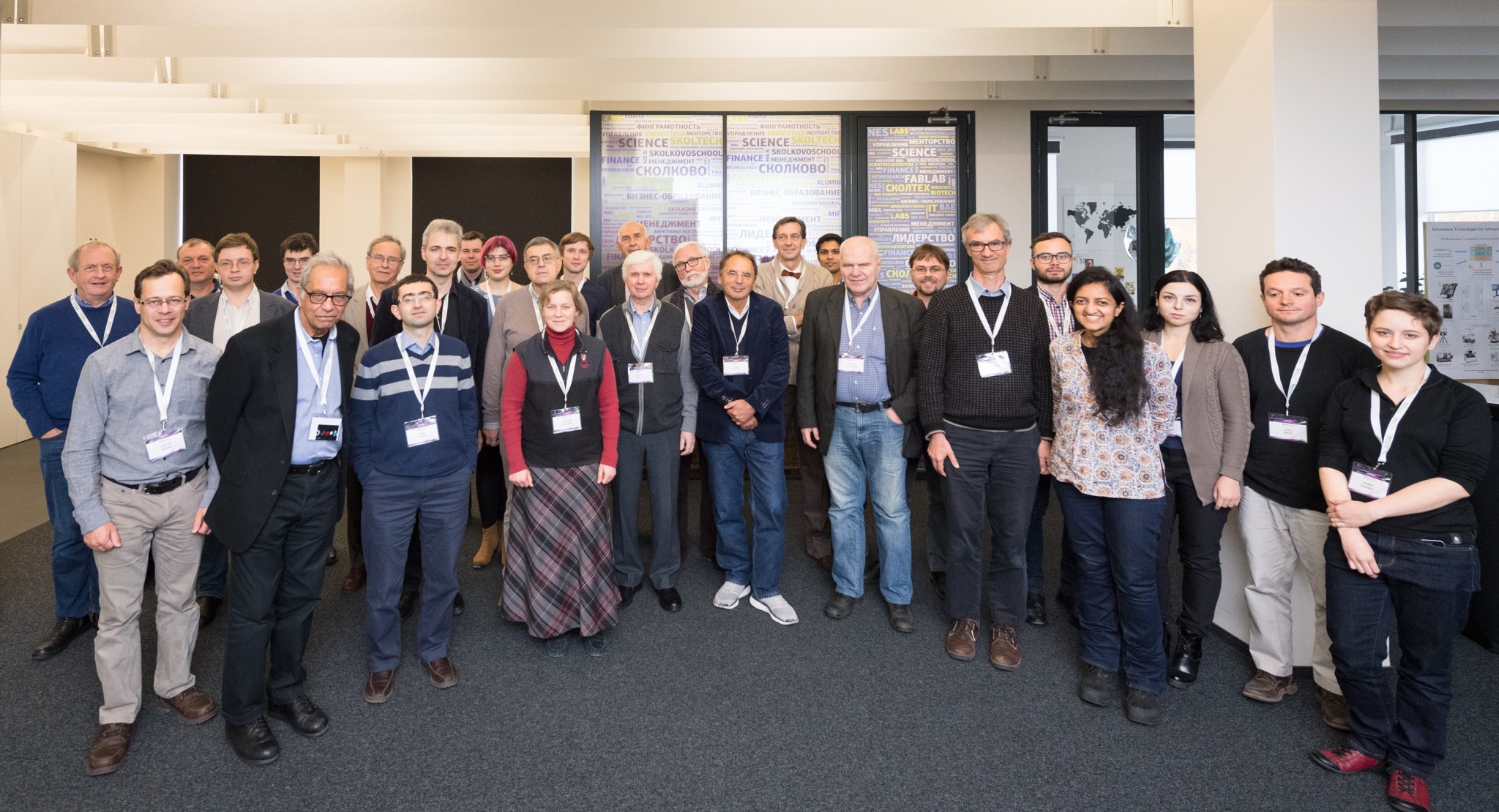

Leading superconductivity scholars from around the globe congregated on campus last week for an international symposium led jointly by physicists from Skoltech and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

The event, organized by Professors Boris Fine of Skoltech and Nuh Gedik of MIT, was called “Perspectives on High-Temperature Superconductivity.”

Superconductivity: what is it and why should we care?

Discovered just over a century ago by Heike Kamerlingh Onnes and researched intensively ever since, superconductivity – the state of transmitting energy without dissipation – remains shrouded in mystery. Traditionally, materials that are capable of superconducting – superconductors – have been known to do so only at extremely low temperatures – a few degrees Kelvin above absolute zero, which is -273° C.

In the late 1980s, two physicists – J. Georg Bednorz and K. Alex Müller – shattered this belief with their discovery that copper-containing ceramic cuprates could superconduct at much higher temperatures. The best performing cuprates superconduct at temperatures of up to 153 Kelvin (-120 ° C) , which, while still extremely cold, is significantly higher than previously thought possible.

In 2015, a group of researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Mainz, Germany, discovered that under extremely high pressure, hydrogen sulfide samples could superconduct at a record high temperature of -70° C. A co-author of this groundbreaking study, Mikhail Eremets, was in attendance at the Skoltech symposium.

In the view of Skoltech’s Fine, superconductivity is of critical importance. “High-temperature superconductivity is one of the frontier subjects of physics and technology today, in part because of its potential applied importance; that is – the promise of the subject to eventually develop room-temperature superconductivity. If this happens, it will be a paradigm-changing technology,” he said, adding: “It’s only a matter of time before something that can superconduct at room temperature is discovered. That’s my belief, and it’s shared by many.”

At present, laboratories worldwide are scrambling to identify a material capable of superconducting at room temperature. Such a material could revolutionize global energy use, storage and production – affecting everything from how we charge our mobile phones to how we distribute power to remote villages.

Fine also remarked that uncovering the superconductivity mechanism in high-temperature cuprate superconductors is among the greatest intellectual challenges physicists have faced in recent decades. He said: “Many – if not most – of the leading physicists working in solid-state physics have tried to solve this problem, but so far we are very far from a scientific consensus.”

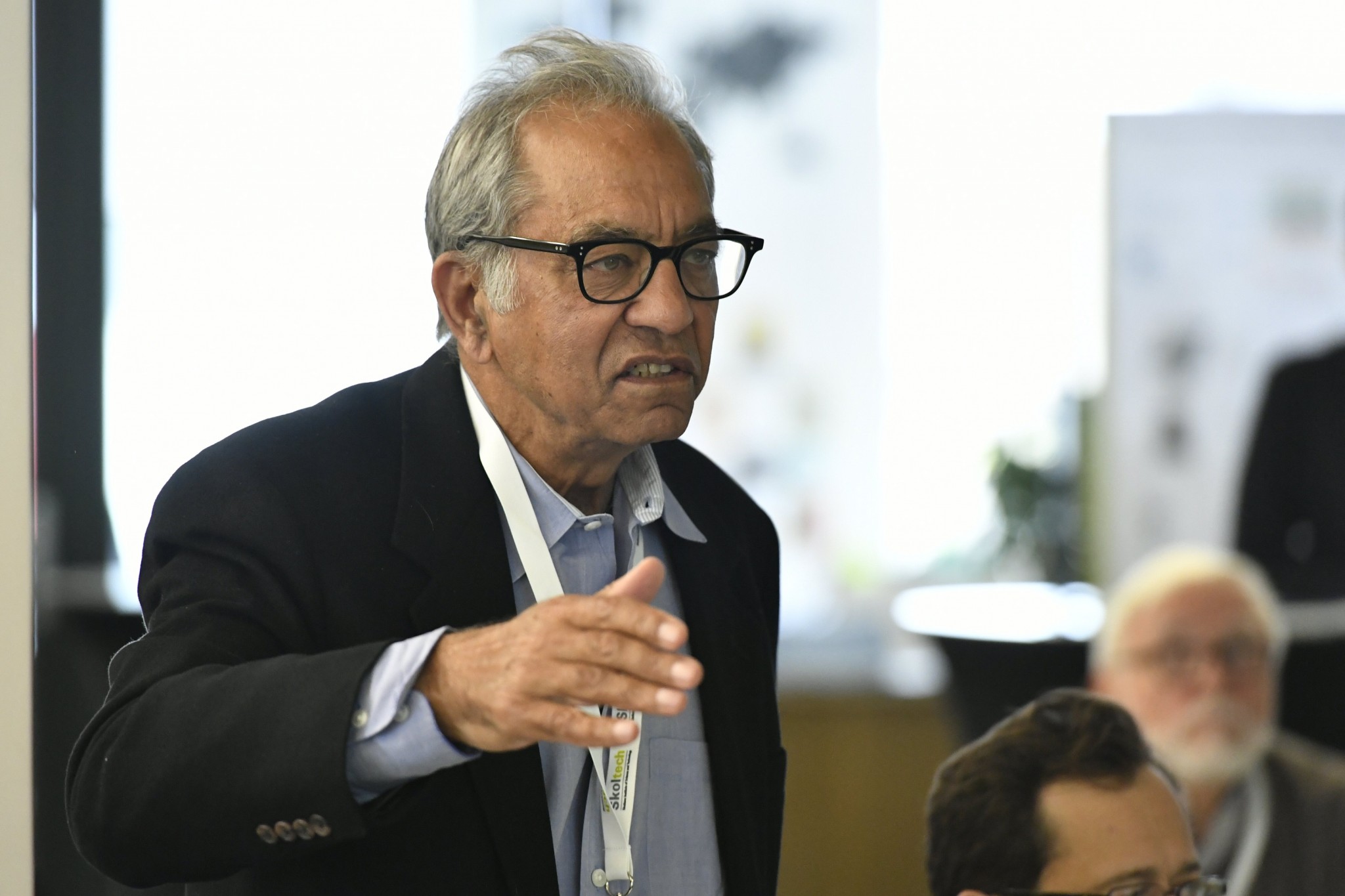

Chandra Varma, a professor at the University of California, Riverside (UC Riverside) and the winner of the prestigious John Bardeen Prize in 2012, echoed this sentiment on the sidelines of the symposium. “This is one of the most important problems in physics of the last 25 years, because it has very deep theoretical issues – very important problems, which are being solved slowly,” he said.

Russia in particular has considerable roots in the fields of superconductivity and superfluidity, including contributions from Nobel-prize winning physicists Pyotr Kapitza, Lev Landau, Vitaly Ginzburg and Alexei Abrikosov, and many others.

As explained by MIT’s Gedik: “For the past 100 years, Russian scientists contributed enormously to the development of superconductivity both in experiment and theory. In that sense, many of the things that we understand in the field originated here.” He added that part of the reason he and Fine chose to host the conference at Skoltech was to celebrate the achievements of Russian scientists in the field.

As a part of this celebration, the symposium included a special session commemorating the work and life of Ginzburg

A meeting of the field’s great minds

In organizing the event, Fine and Gedik hoped to create a venue for discussions of recent progress in the field.

This is a matter close to both of their hearts; in 2016, they received a Skoltech-MIT Next Generation Program grant to conduct research on high-temperature superconductors. As part of their joint project, Fine and Gedik have spent time at each other’s institutes and have overseen student exchange programs. This symposium was also a part of their collaboration.

By all accounts, the attendees were thrilled with the outcome.

“I learned a lot and I’ve had some really good conversations,” said Harvard Professor Jenny Hoffman. “I’ve sent numerous emails to my students with new thoughts and ideas over the past two days.”

Hoffman, who uses custom-built scanning tunneling spectrosopy probes to study high temperature superconductors and other exotic materials, said that for her the highlight of the symposium was the opportunity to learn about the similarities and differences between her own lab’s findings and those of other leading labs.

Professor Davor Pavuna of the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) said that he was impressed with the concentration of highly accomplished researchers in attendance at the symposium.

“The most important outcome is to bring different experts together, and that was a huge success. The organizers brought together colleagues from across Asia, America and Europe… We got representatives of all the necessary knowledge areas – from theory, to experiments, to materials, to applications. To have such constructive knowledge in just two or three days is a great success for Skoltech,” said Pavuna, whose primary research area is in the development of superconductors.

École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne Professor Davor Pavuna (left), alongside Professor Sergey Ovchinnikov of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Photo: Skoltech.

Varma of UC Riverside shared Pavuna’s enthusiasm about the invitees. “There are lots of people here who I wanted to meet, and I was glad to be invited to come and speak and to listen to them. There have been some very interesting talks and very interesting results – completely new results which I hadn’t known before,” said the professor.

Several of the attendees interviewed for the story described the opportunity to meet leading experts as a highlight. And not only experts from the other side of the world – Harvard’s Hoffman noted the irony of having heard about her colleague Riccardo Comin’s recent research in Russia via a Skype presentation that he delivered from his office at MIT; Harvard and MIT are about a mile away from each other in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Gedik likewise mentioned that despite the fact that Hoffman’s lab is about 20 minutes away from his by foot, he only learned about her latest research at the Skoltech symposium.

Eremets of the Max Planck Institute lauded the small size of the conference. “I like this kind of conference which is smaller in size because it gives you the opportunity to talk with people very closely. Sometimes small conferences are more beneficial than big ones,” he said.

Mikhail Eremets of the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Mainz, Germany. Photo: Carsten Costard // Max Planck Institute.

Pavuna of EPFL also said he was thrilled with the level of all of the speakers’ presentations: “The quality was as good as it gets. The talks were very well prepared, and the discussions were friendly, and I only wish there will be more meetings like this.”

Eremets added that one thing he particularly enjoyed about the symposium was the opportunity to experience Skoltech and the greater Skolkovo ecosystem from the inside.

“I knew about Skolkovo and really wanted to see what was here – how it’s arranged, how it works, how it looks, to talk with its faculty members and students,” he said, adding that he was pleased with what he discovered. “People are very happy that they work here. That’s very clear. I’m really impressed. It’s wonderful that in Russia such things are developing.”

This being his first visit to Skoltech, Gedik was likewise impressed: “This is my first time at Skoltech and I’m very much positively impressed by the potential of the university.”

Fine was pleased with this outcome, observing that Skoltech has clearly made a good impression on the intellectual leaders of the community working on high-temperature superconductivity.