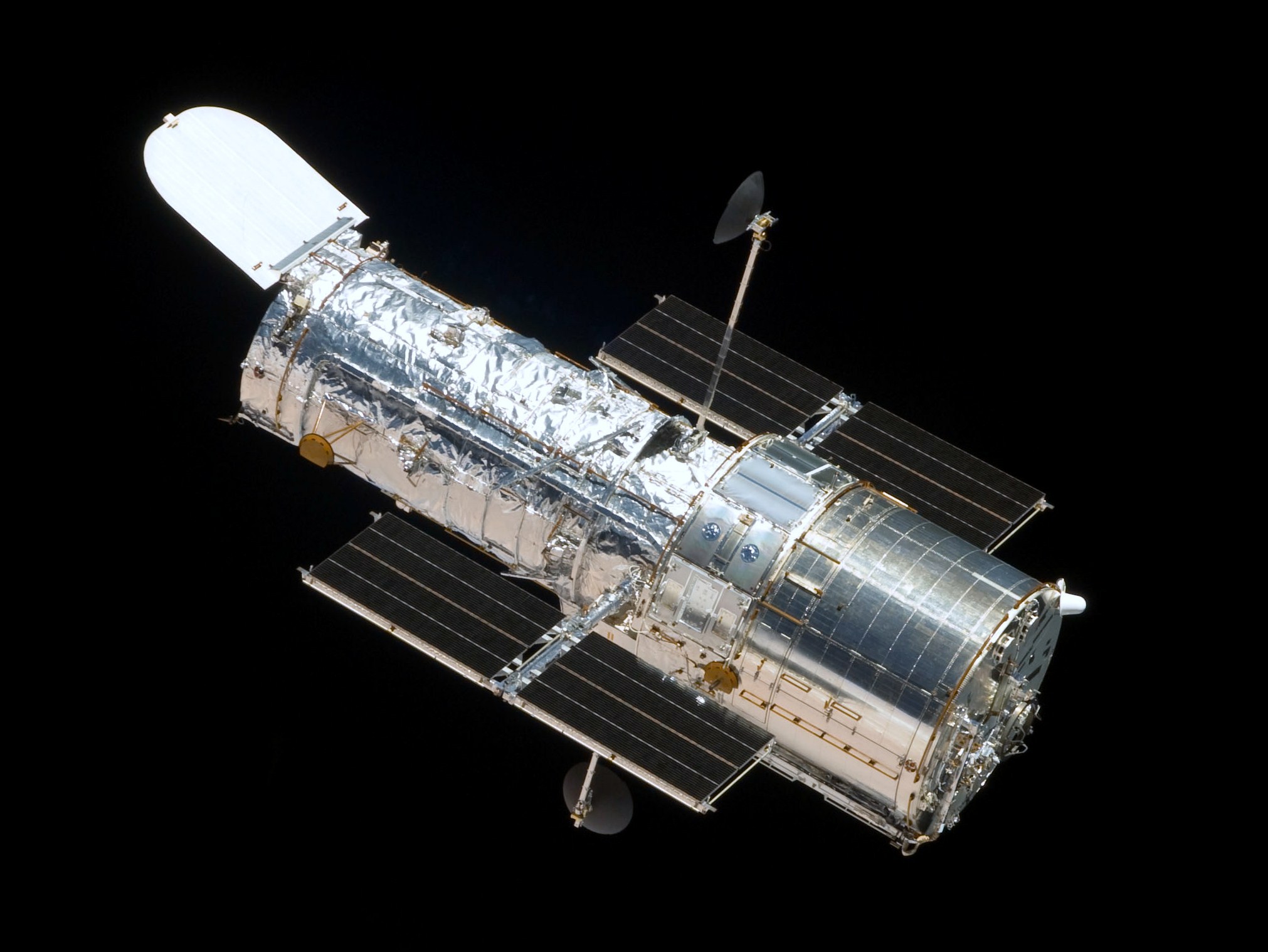

During the recent SpaceUp unconference, Skoltech hosted a panel of space experts that included the first Swiss astronaut, Claude Nicollier, who famously took two missions in the 1990s to help repair the Hubble Space Telescope.

Throughout his life, Nicollier’s dual passions for astronomy and flight have led him to blaze countless trails, carving out a legendary career that young space enthusiasts around the globe dream of emulating.

On the sidelines of SpaceUp, Nicollier told us all about the spacewalk experience, and shared some encouraging words on how we all might live more meaningful lives.

When and why did you decide you wanted to become an astronaut?

I was always interested in the sky. Even as a kid I was looking at stars and trying to photograph them with an old camera. I would attach the camera to a telescope and tracking stars to make long-exposure shots of the sky.

I also had an interest in aviation. I was building model airplanes, and I had a double passion for the sky and airplanes. And I decided to study Physics and Astrophysics, and was also accepted into the Swiss Air Force as a pilot, which was a part-time activity.

When Gagarin flew in space, I was 17 years of age, so I was a young man. I was just about to start my studies.

At the time, I realized that Astronautics was between the Soviet Union and a little bit later, the United States; it was these two nations, so there was no way for a Swiss person to become an astronaut or cosmonaut.

So I focused on my interests, which were astronomy and aviation. I studied Astrophysics, worked as an astrophysicist, and was flying a fighter jet every two months or so. So I was a happy young man because I was doing things I liked.

Then we had the Apollo program. I was 25 years of age when Apollo 11 took place – it was fascinating. But again, this was done by people of other nations, not by the Swiss or Europeans.

But then in 1975, ESA was invited by the United States to participate in the shuttle program. And at the same time, they could select astronauts to fly on the shuttle.

Immediately I decided this was the route I wanted to take.

What was the selection process like?

I applied for the selection. I was invited to a series of interviews, and I prepared for each interview like it was a university exam. I knew there were going to be life scientists and medical doctors there, so I wanted to make sure I would not give stupid answers to their questions.

And it worked. I think they saw my determination and my readiness to learn new things, and I was accepted in 1978.

Tell us about preparing for your first flight

After I was selected, there were two years of scientific training in Europe, and then we were sent to the United States – to Houston. There were three of us in total, and my other two colleagues went back to Europe and trained for Spacelab flights. The Spacelab was a laboratory to be installed in the payload of the shuttle. It was a European contribution.

Meanwhile, I stayed in Houston and trained on the shuttle. I was the first non-American to do that.

I trained in Houston for 12 years until my first flight.

I was supposed to fly in 1986, but the flight was cancelled after the Challenger accident, so my flight was delayed for six years.

It was a long time, but I had a lot of things to do. I was a totally happy person over there [in Houston].

I didn’t have much priority because I was one foreigner among a group of about 120 American astronauts, but I was making my way. I was working hard. And then I got my first flight, and immediately afterward I was scheduled for my second flight. And then I went on to complete my third and fourth in eight years, which is a pretty short time.

I never left behind my passion for astronomy and aviation. I still fly in Switzerland, and every opportunity I have to participate in discussions on astronomy. So I did not become an astronaut and forget about my other interests; I focused on my astronaut activities, but I remained very much with my heart and brain and soul a pilot and an astronomer.

Why were you chosen to repair Hubble?

I believe I was chosen because my first mission went well, and they saw that I had huge motivation.

Being selected for the Hubble repair mission was a huge privilege for me, because it had been a bit of a pity for me to leave astronomy, and I was then given the chance to work for astronomy as an astronaut.

What was your first experience with Hubble?

I had my first visit to Hubble during my second flight, because it had these big optical problems that we had to fix. I didn’t spacewalk on this mission; I was a robot arm operator and flight engineer. But the spirit of the mission was wonderful, because Hubble was broken and we had to fix it so that it would work perfectly.

On my fourth mission I returned to Hubble to change gyroscopes and a computer. This is when I did my spacewalk.

What went through your mind when you first stepped out into open space?

You train a lot, and you try to never be too emotionally involved, because you have a tough task to accomplish. Every spacewalk is prepared nearly minute-by-minute. There were two of us, and we optimized the locations for each of us in order to do the maximum amount of work in the shortest possible time.

So you cannot be too emotionally involved; you have to do your job, but of course the view is absolutely incredible.

What was the spacewalk process like?

I was the first one of the two of us to come out. We had a safety tether between us and then I came out and attached my safety tether [to the shuttle], and then my colleague’s, and then I was able to detach the link between the two of us.

We had practiced this a lot, but first of all you need to do these things, and not just look at stars and the Earth.

In all, they gave me five minutes – like they do for every first-time spacewalker – where I didn’t have any work to do. I was able to just move around freely to get accustomed to moving around in space. Five minutes is very short; it was just enough time to look around and move around the handrails.

Of course we practiced this before the flight in the water, but water is different. You can swim in the water; you cannot swim in space.

After that, it was time to start working.

I went to my position and my colleague went to another, and we had to exchange a computer at one point. This is what spacewalks are like; for the most part you just power through your work, but every so often, you look up and see special features on Earth like Egypt and the Red Sea and the Nile Delta moving rapidly under you. You look for 10 or 20 seconds, and then continue working.

Sometimes you have a spacewalk where you have to wait, but there was no waiting on our mission. It was all done in one shot of pretty intense activity.

We had some problems with inserting a new camera into the telescope and we had to find a new way to do it, so we had a bit of preoccupation and stress, because we had eight and a half hours maximum. Our spacewalk finally lasted eight hours and 10 minutes, so it was pretty close to the limit.

For me it was wonderful, but mainly because we accomplished what we had to accomplish, and in addition, the view was superb.

You know, we are nearly obsessed with being successful on the mission. And every spacewalk is part of the mission, so we want to be successful on each spacewalk. And this one had little margin for completing the planned task.

For drinking, I had a bag of water, but that was all – no food or energy drinks. It wasn’t enough water; I remember being very dehydrated by the end of the spacewalk because it’s physically very, very hard and we went five times around the Earth in these eight hours.

Every time after sunset, it became extremely dark except where our workplaces were illuminated with our helmet mounted floodlights.

I have very clear memories of this spacewalk. It was a little stressful – you always feel that you’re under pressure, but we could do all what was planned and it was a huge satisfaction at the end

Was it difficult for you to leave space for the last time?

Every time we left Hubble behind on a repair mission, it felt like parting ways with an old friend.

But I didn’t have a particularly difficult time the last time I left because I didn’t realize it would be the last time.

I was on the third Hubble repair mission and there were two more afterward. When I came back, the plan was for me to have another mission – either to the International Space Station (ISS) or to Hubble.

And then the [Columbia disaster] happened in 2003, and of course accidents like this are always tragic because you lose your friends.

But after that, another flight was no longer an option for me. So I stayed on and worked in Houston a little while longer, and then in 2005 I returned to Europe.

What advice would you give to aspiring young astronauts?

Of course being an astronaut is a fantastic job, but there are also plenty of people who become happy engineers, or airline pilots, or carpenters.

I think the main thing is to really try to see in yourself where your passion is, and to follow that path and not let yourself be distracted by other things.

For me, it was this double passion for astronomy and aviation that converged into my job as an astronaut – especially the space shuttle, because it was like an airplane going out of the atmosphere. So my passion for aviation was satisfied with the space shuttle.

But whatever the field is, follow your passion and work hard in order to be successful and be one of the best in your area.

I always try to tell my grandchildren to try to excel – to try to be the best in their class – without being arrogant at all, rather trying to work quietly to be the best.

And always follow the direction that is in your heart. Sometimes it’s hard to see because there are a lot of distractions, but sometimes you need to close your eyes and think about what there is in yourself that’s driving your life. There’s always something. You have to follow that and work hard in order to become one of the best ones in your area.

I don’t pretend I was one of the best ones, but you have to try. If you try, you at least end up at a pretty high level.

But at some point, you have to cut out the distractions and try to see in yourself what is driving your life. Sometimes it’s driving your life rather secretly, but you need to expose that and follow that road.

Make silence in yourself to see the real reason for your life – for the 60, 70, 80 – 100 years you have to spend on planet Earth and beyond.

Nicollier snaps a selfie with Skoltech MSc student and SpaceUp organizer Shreya Santra, as well as cosmonaut Sergey Revin and fellow astronaut Jean-Jacques Favier. Photo: Skoltech.