French astronaut Jean-Jacques Favier traveled into space in 1996 aboard the Space Shuttle Columbia, pictured here at takeoff. Photo: NASA; cropped by Skoltech.

During the recent SpaceUp unconference, Skoltech hosted a panel of space experts that included French astronaut Jean-Jacques Favier, who in 1996 logged upwards of 405 hours aboard the Space Shuttle Columbia.

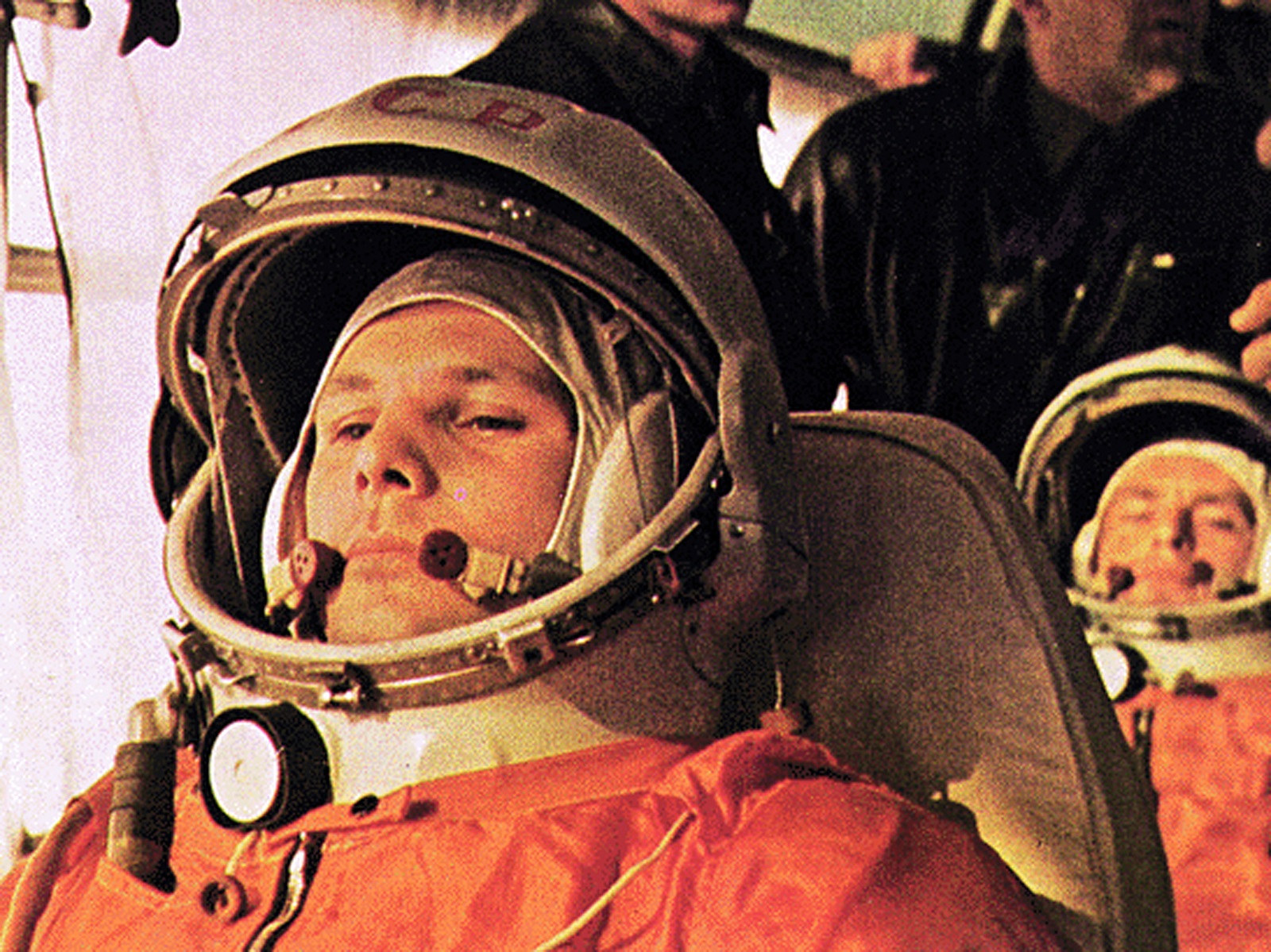

Yuri Gagarin’s iconic first human spaceflight left an indelible mark on Favier – then a boy of 12. He went on to become a physicist and engineer, designing experiments that professional astronauts would fly to space, all the while wishing he could conduct these experiments himself.

As soon as it became possible for European scientists to fly to space, Favier leapt at the opportunity.

On the sidelines of SpaceUp, Favier told us all about his path to becoming an astronaut, and shared some of the unexpected insights he gained from his journey into the cosmos.

Why did you decide you wanted to become an astronaut?

Yuri Gagarin flew on the eve of my 12th birthday. And that really resonated with me. So I followed developments in human spaceflight after that – both Soviet and American. But I never dreamed that one day I would be a part of it.

I pursued my studies in physics and engineering, but I was always attracted by space.

As a young researcher in the 1970s, I used to prepare a lot of space experiments and I was a little bit frustrated because rather than completing them myself, I would offer them to professional astronauts who would then take my experiments into space with them. Back then, space agencies primarily sought pilots, but eventually they opened the selection up to engineers and scientists, and once that happened, I thought, “Why not me?” So I applied.

At that time, I was 35 years old, and it would be another 11 years before I took my spaceflight.

What was the selection process like?

I applied at the French level first, and was selected by the French space agency [Centre national d’études spatiales or CNES]. I was then supposed to fly either with the Russians, on Mir, or with the Americans. So I started my training here in Russia, but it only lasted for about six weeks – until we started training on the Soyuz capsule – and then they discovered that at 193 cm., I was too tall to fit into the Soyuz. The seats were designed for pilots – who at the time, tended to be on the shorter side.

So the only way for me to fly was to approach NASA and the Americans, because there was more room in the space shuttles.

I joined NASA in 1992 as a scientist and researcher during a sabbatical year. It had just opened a selection for scientists, so I applied, and I was selected as a backup astronaut.

The training to fly in the space shuttle took three years from the start to the last medical exam. Six months later, I was assigned as [a payload specialist] on a new mission, and after another 18 months of training, I took my first flight.

What was the most challenging aspect of being in space?

The shuttle is not the space station; it’s actually a very small space compared to the International Space Station. And seven of us were up there at the same time. So the size of the inside of the shuttle was comparable to a small school bus. You have to live and work with your colleagues in these conditions for a long period of time.

In the space station, there’s comparatively plenty of space, so if you don’t want to see your colleagues for a day or two, you can move to another module.

So in the shuttle, it was crucial to have good relationships with the crew. They taught us about this during training, and actually during the selection they were looking for people with strong abilities to get along well and work with others.

And generally this worked out. As far as I remember, almost none of the shuttle crews suffered from interpersonal problems.

When everything is ok – when the mission is nominal, as we say – there generally aren’t any problems. But when the mission is non-nominal, and tensions rise, sometimes there can be problems between people.

This can be true among crew members, or between crew members and mission control.

Human space exploration is first and foremost a human venture, so the human aspect of the mission is imperative. You need to have the sort of character that will allow you to be part of the team – and I don’t just mean the team of astronauts. For every six crew members you have in space, you have more than 800 engineers working from the ground, and they are all part of the team. So you should have good relationships with them too.

The crew of STS-78. Back, from left: Favier, Richard Linnehan, Susan Helms, Charles Brady and Robert Brent Thirsk. Front, from left: Terrence Henricks and Kevin Kregel. Photo: NASA.

What’s the most incredible aspect of being in space?

For a scientist like me, it was being able to conduct my own experiments in space. That was very exciting from a professional point of view. Basically, I brought my experiments full-circle. I prepared them in the lab, I developed the flight models, I flew the flight models, and then after the mission I brought them back to the lab to exploit the data, and then made publications.

I’m one of very few people who has been able to do that.

What advice would you give to young researchers who hope one day to become astronauts or cosmonauts?

After I left NASA, I became a full professor at the International Space University near Strasbourg, France. I used to always tell my students to never give up. But at the same time, I advised them not to have the singular goal of becoming astronauts – because the probability is so small.

For those who wish to become astronauts, I would advise you to develop an interest in doing things around the space program – as an engineer, scientist, or whatever – and the cherry on the cake would be to become an astronaut. But that should not be the singular goal

And that’s what I did myself. I was a physicist for 30 years, but I had in the back of my mind the possibility that I could one day become an astronaut. When I began to see that other people with profiles similar to mine were flying to space, I thought I should give it a try.

So I worked hard, but I was also very lucky. Luck is always part of the deal.

But, if you have a dream, whatever it is, if you don’t give up, you will make it.

What is it that drives you to attend conferences that are geared toward budding space professionals like SpaceUp?

Since my spaceflight, I’ve attended conferences with all sorts of people – from kindergarteners, to high school and university students, to members of the public at large. But especially young people. That’s because I want to inspire young people to pursue scientific education.

There are fewer and fewer young people going into scientific studies; people are more interested in business and making fast money. That doesn’t work most of the time.

So I think there’s so much to do in science at large, and space is a good example of something you can invest your time and passion into.

So I like to speak to young people. This is why I became a professor.

And I have two passions: teaching and research. Toward that end, conferences like SpaceUp offer a good opportunity for me to be in contact with students and young scientists.

You have always strongly emphasized the importance of fundamental science in spaceflight. Would you say that field scientists such as geologists and biologists are as important as rocket engineers on spaceflights?

If we think of future human missions, such as going to the Moon or Mars for long-duration or permanent missions, I think scientists will be very, very useful and important.

The last Apollo flight – Apollo 17 –was the only Apollo flight with a real scientist on board. [Harrison Hagan] “Jack” Schmitt was a geologist. While he was on the moon, he selected the best rock samples to bring back to Earth because he had expertise in the matter.

In all, the Apollo missions brought back something like 500 kilos, but the best 50 came from Schmitt.

For the future of human exploration – be it to the Moon or to Mars – I think having a scientist on board will be of critical importance.

That said, of course, the astronauts will have to be multi-profile. Perhaps this will change if we’re there for an extended period, but at least for the next 20 to 30 years, we’ll need to have astronauts who can wear at least two hats – i.e. biologists/mechanical engineers, or physicists/medical doctors, and so on.

Did your time in space change the way you see the world?

When you fly, you realize that you are very, very lucky to be there. Looking out the window at Earth and realizing how very beautiful the planet is – it’s a very blue planet, I can tell you. This is something that you have to communicate with the people back on Earth after your flight.

I felt it was my responsibility to tell people that the planet is very, very fragile, because I could see the pollution from space. I could see smog and fires. What surprised me most were fires in the Amazon Rainforest – this is real deforestation. On any continent you would see fires – in California, Africa, Europe, Australia – but it didn’t compare to the Amazon Rainforest.

Someone in Europe who has never been to South America may be totally naïve to the fact of the terrible deforestation in the Amazon Rainforest, but looking at it from the spacecraft, it takes seven minutes to go from the Amazon to Europe. From that perspective, it all seems to be one small village.

This is something that changed my mind. I became more environmentally aware after seeing these things with my own eyes, and realizing the fragility of the planet.